Where the Visible and Invisible Meet: A Conversation with Kendra Larson

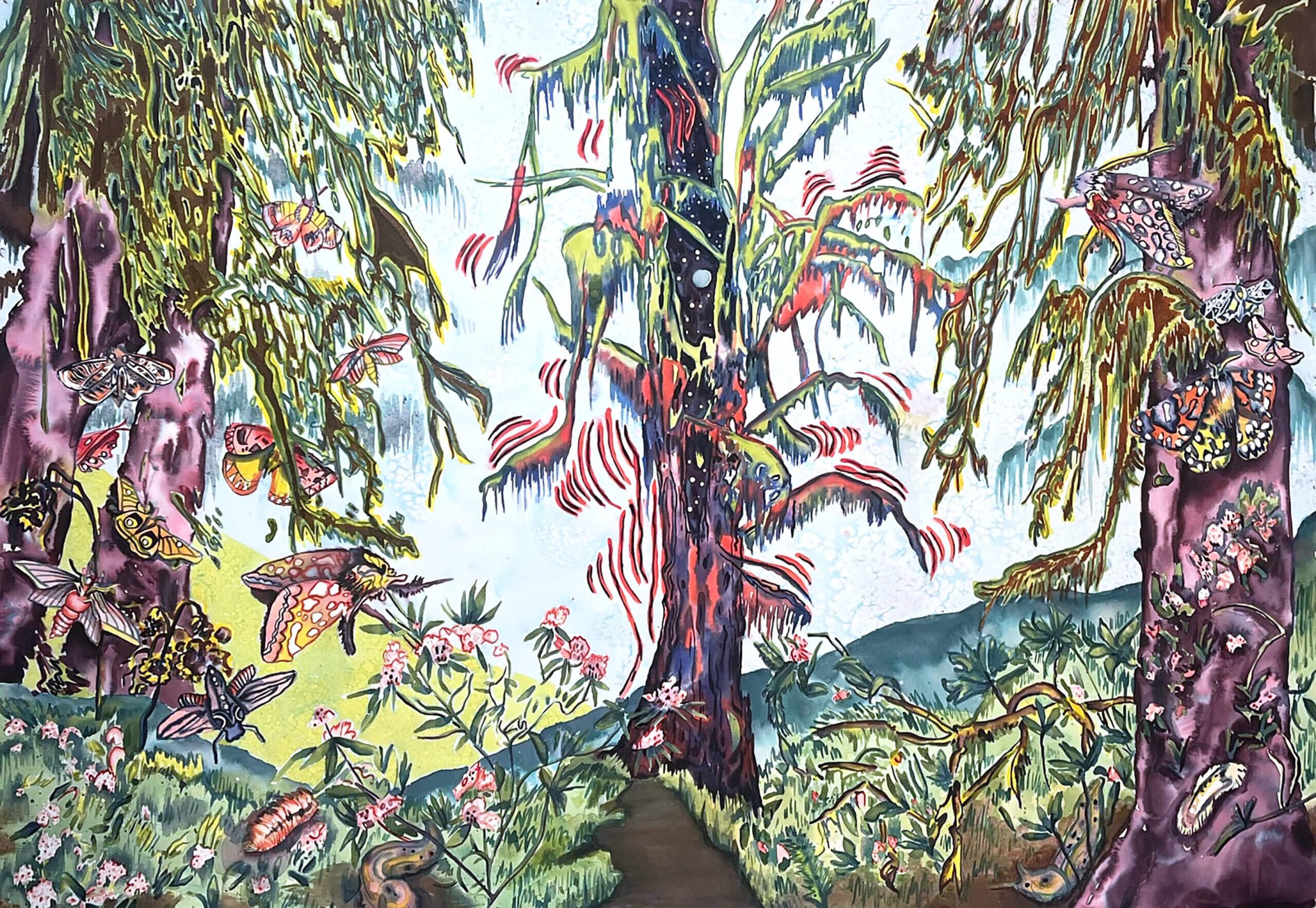

Kendra Larson is an artist based in Portland, OR with a primary focus on the ephemerality of Pacific NW landscapes. Her work explores historical ideas of the Landscape and subtly supports ideas around environmentalism as well as contemporary relationships with the natural world.

Larson grew up in Salem, OR. She received her MFA in Painting at University of Wisconsin, Madison and has shown her work in venues in the United States and New Zealand. Larson is a past Signal Fire, Caldera (Sisters, Oregon) New Pacific Studios (Masterton, New Zealand), Sitka Center for Art and Ecology (Oregon), and Fish Factory Creative Centre of Stöðvarfjörður (Iceland) artist in residence. Larson teaches at Clark College and is the Archer Gallery Director. She is represented by Augen Gallery in Portland, OR and AMcE Creative Arts in Seattle, WA.

Learn more: www.kendralarson.com

You describe your work as exploring the ephemerality of Pacific Northwest landscapes. What first drew you to this subject matter, and how has it evolved over time?

I was initially drawn to forests as places of quiet observation, but the more I learned about how trees communicate and support one another, the more my relationship to landscape shifted. Reading about the hidden networks beneath forests helped me see these spaces as living, intelligent systems rather than static backdrops. Over time, my work has become less about documenting place and more about translating what it feels like to be in relationship with it (emotionally, psychologically, and spiritually).

Your paintings often make visible fleeting elements such as smoke, fire, and clouds. What draws you to these temporary qualities, and how do they function conceptually in your work?

I'm really interested in things that don't stay still. Smoke, fire, and clouds feel like moments of transition. They're beautiful, but they're also unstable and impossible to hold onto. In a way, this parallels the flaws and exciting challenges of painting. Conceptually, these ephemeral things allow me to talk about impermanence and vulnerability, both in nature and in ourselves. They also suggest movement and communication within the landscape, hinting at the unseen systems constantly at work beneath the surface.

Many of your works reference folklore, magic, and mystery. How do these ideas intersect with your interest in environmentalism and place?

For me, folklore and magic are ways of reintroducing wonder into how we think about the natural world. Science gives us crucial knowledge, but myth and mystery help us feel emotionally connected. When a place feels enchanted or alive, we see ourselves reflected in it and are more likely to care. That sense of magic isn't about fantasy. It's about acknowledging that there's more happening in these environments than we can immediately see or measure. And yet, I also love reading folklore and recognize that the characters, traditions, symbols, and motifs find their way into my work… sometimes subconsciously.

You have participated in residencies across the United States and internationally. How have these experiences shaped your understanding of landscape and influenced your studio practice?

Residencies have helped me focus in and really listen to a place. Being immersed in unfamiliar environments sharpens my awareness of atmosphere, light, and emotional tone. Even when the landscapes are very different, those experiences deepen my understanding of how place shapes feeling. I bring that sensitivity back into the studio, where the work becomes a synthesis of many locations filtered through my ongoing relationship with the Pacific Northwest. Plus, being lucky enough to do residencies and often getting funding to do so, makes me want to prove I deserve the accolade. It lights a fire in a way.

The Pacific Northwest plays a central role in your work. What do you feel makes this region distinct, both visually and spiritually, compared to other places you have worked?

Someone once pointed out to me that here in Oregon there are no specific destinations. No Mt. Fuji, no Grand Canyon, and so on, but instead the whole area induces a sense of awe. The air has a specific freshness, and all the conifers lend a certain lush green frame to every view. There's a density here (visually and emotionally) that feels unique. The forests are layered, the light is constantly shifting, and everything feels saturated with presence. Spiritually, there's a sense that the boundary between the physical and the unseen is thin. That openness aligns with my interest in mysticism and awe, and it's something I feel deeply when working in this region.

You balance multiple roles as an artist, educator, and gallery director. How do these positions inform one another, and how do you protect space for your own creative practice?

I enjoy the variety of all these roles, but it has required me to become very disciplined with my time. If I don't have a pressing deadline or something on my calendar, I choose my activity by considering my mind, body, and soul. It's kind of silly, but I ask, "have I neglected any of those things lately?" then proceed with whatever needs my attention the most.

All of these roles are connected through conversation and community. Teaching and directing a gallery keep me engaged with ideas and other artists, which ultimately feeds my own work. At the same time, painting requires solitude and focus, so protecting studio time is essential. I think of the studio as a kind of sanctuary. It's where everything else gets distilled and made sense of.

Looking ahead, what ideas or questions are currently guiding your work, and what can viewers expect to see next from your practice?

Right now, I'm having fun playing with watercolor and narrative symbols. I haven't quite figured out how yet, but I know they have something to do with motherhood and matriarchs. I'm also thinking a lot about awe (how moments of wonder can be healing and how they might help us feel more connected to one another and to the natural world). I'm continuing to explore forests as both intelligent ecosystems and emotional mirrors. Moving forward, the work will keep pushing toward that space where the visible and invisible overlap, inviting viewers to look closely and reconsider their relationship to place.