Becoming Feral: The Unreliable Archive of Memory and Motherhood, An Interview with Darcy Whent

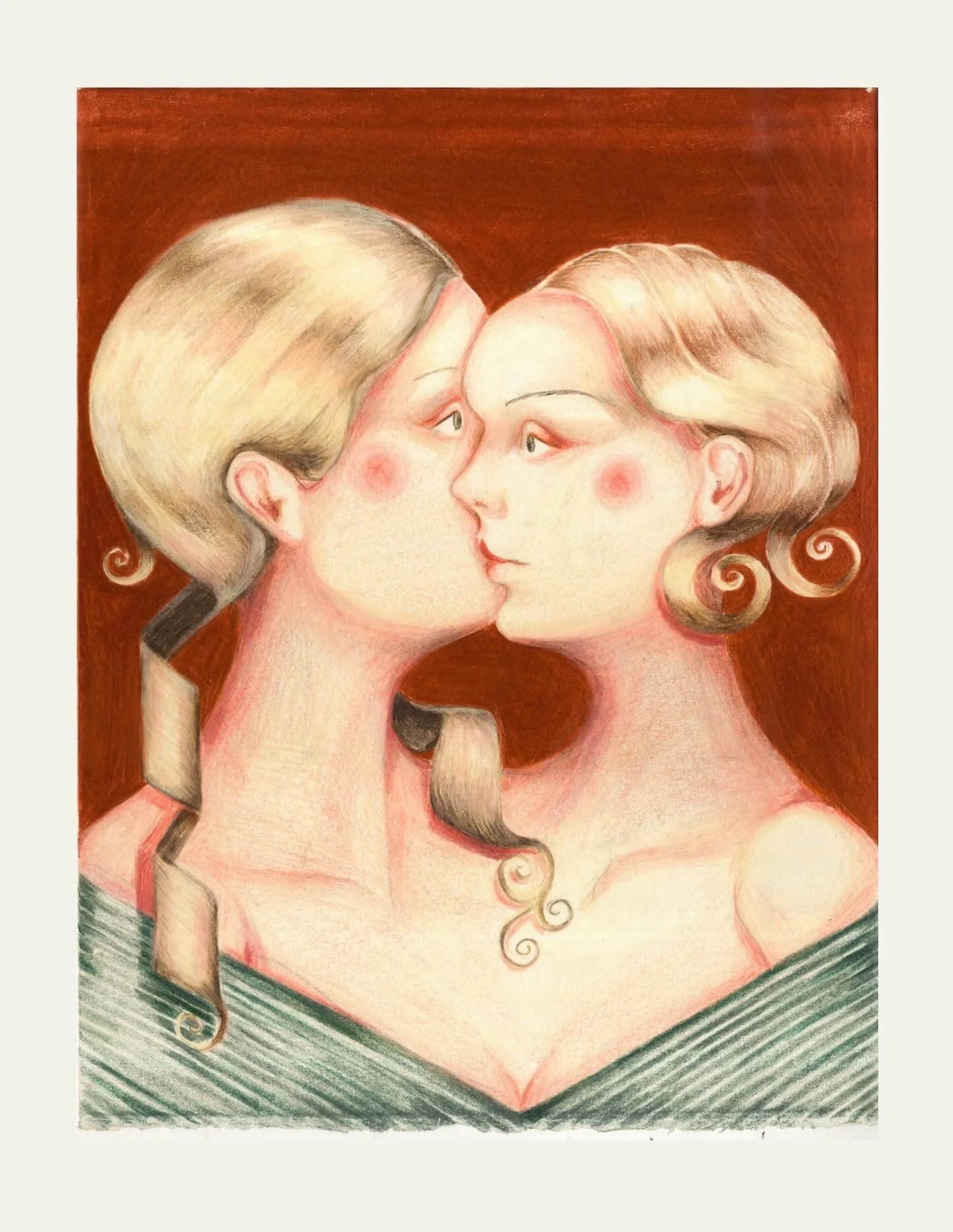

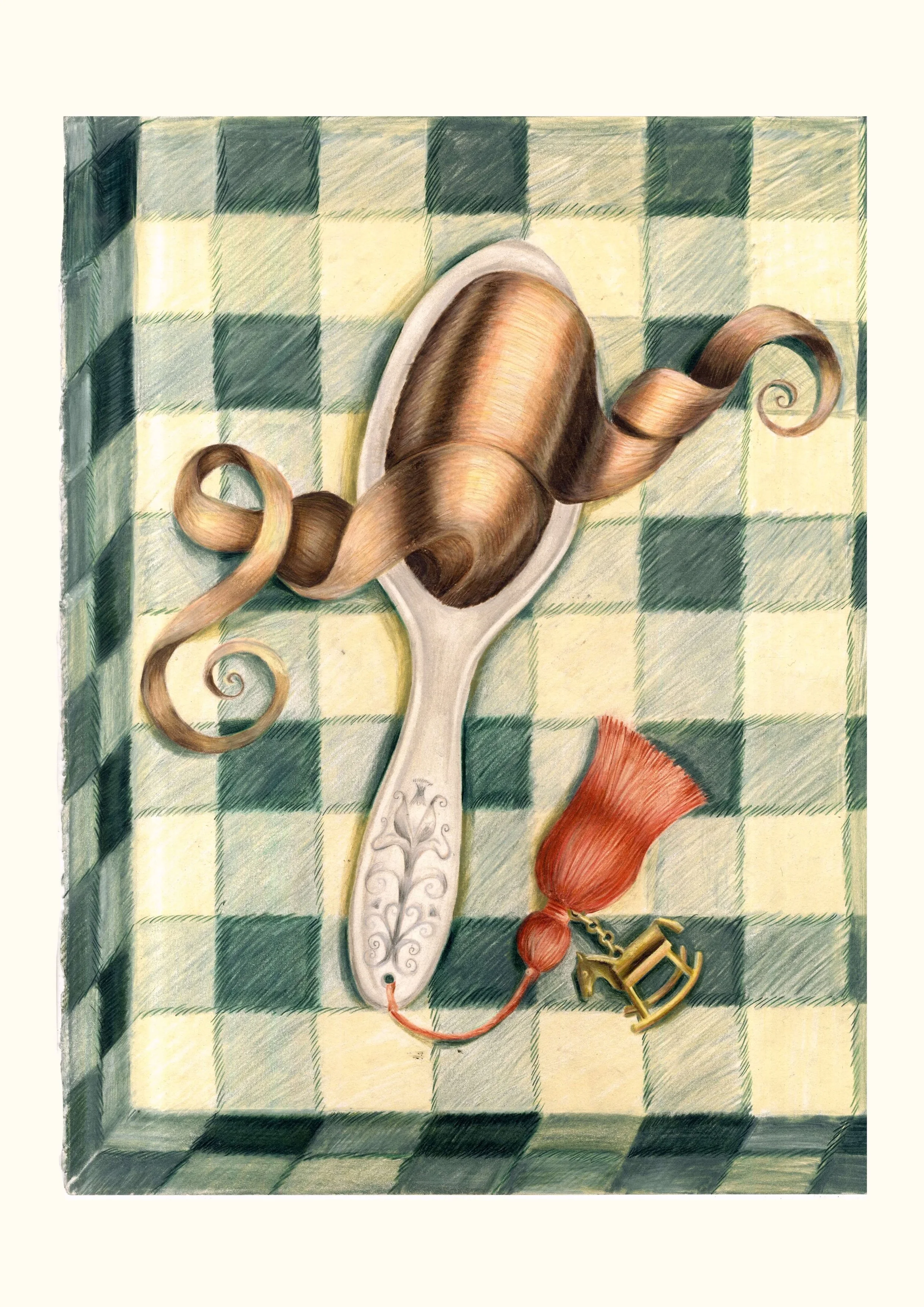

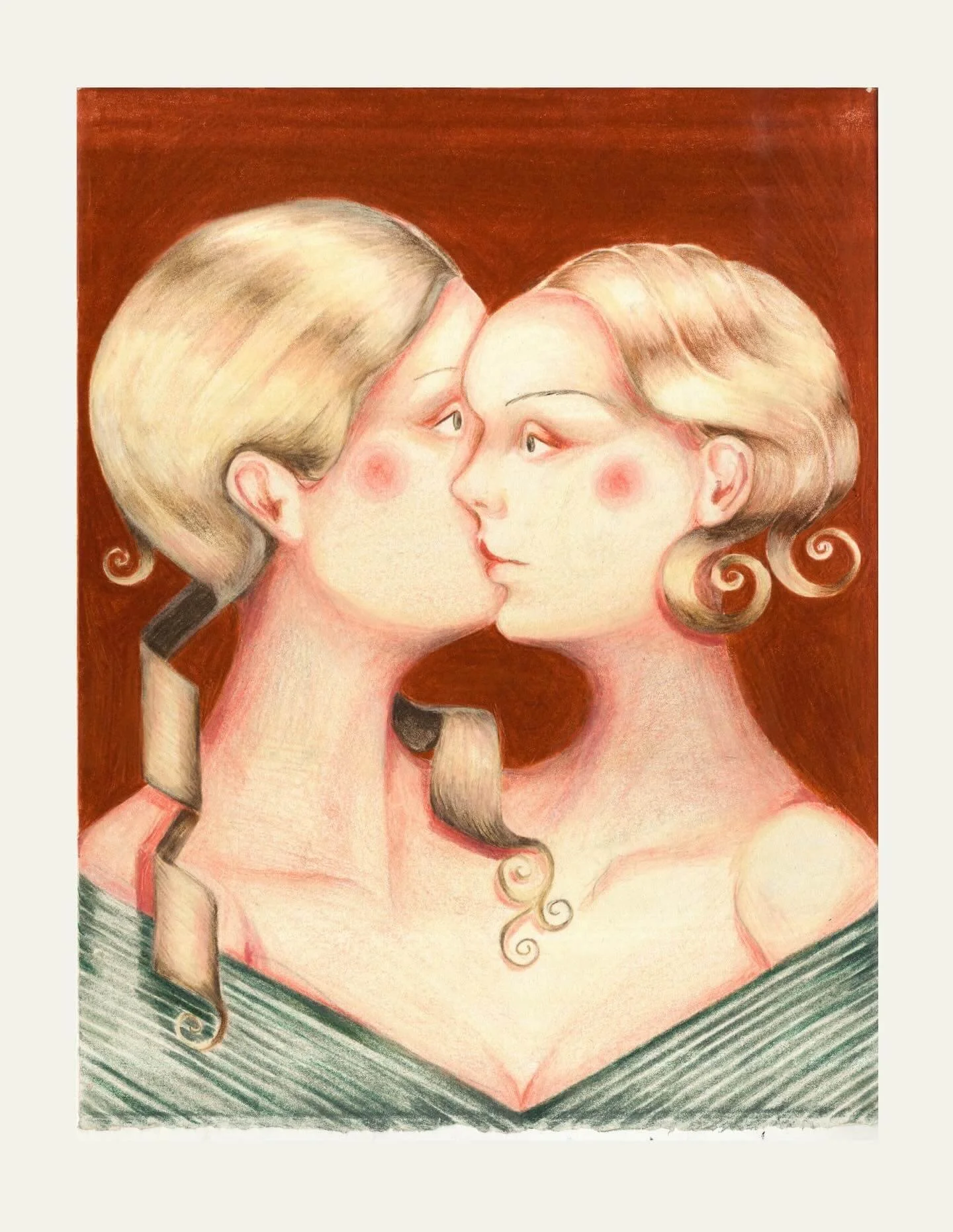

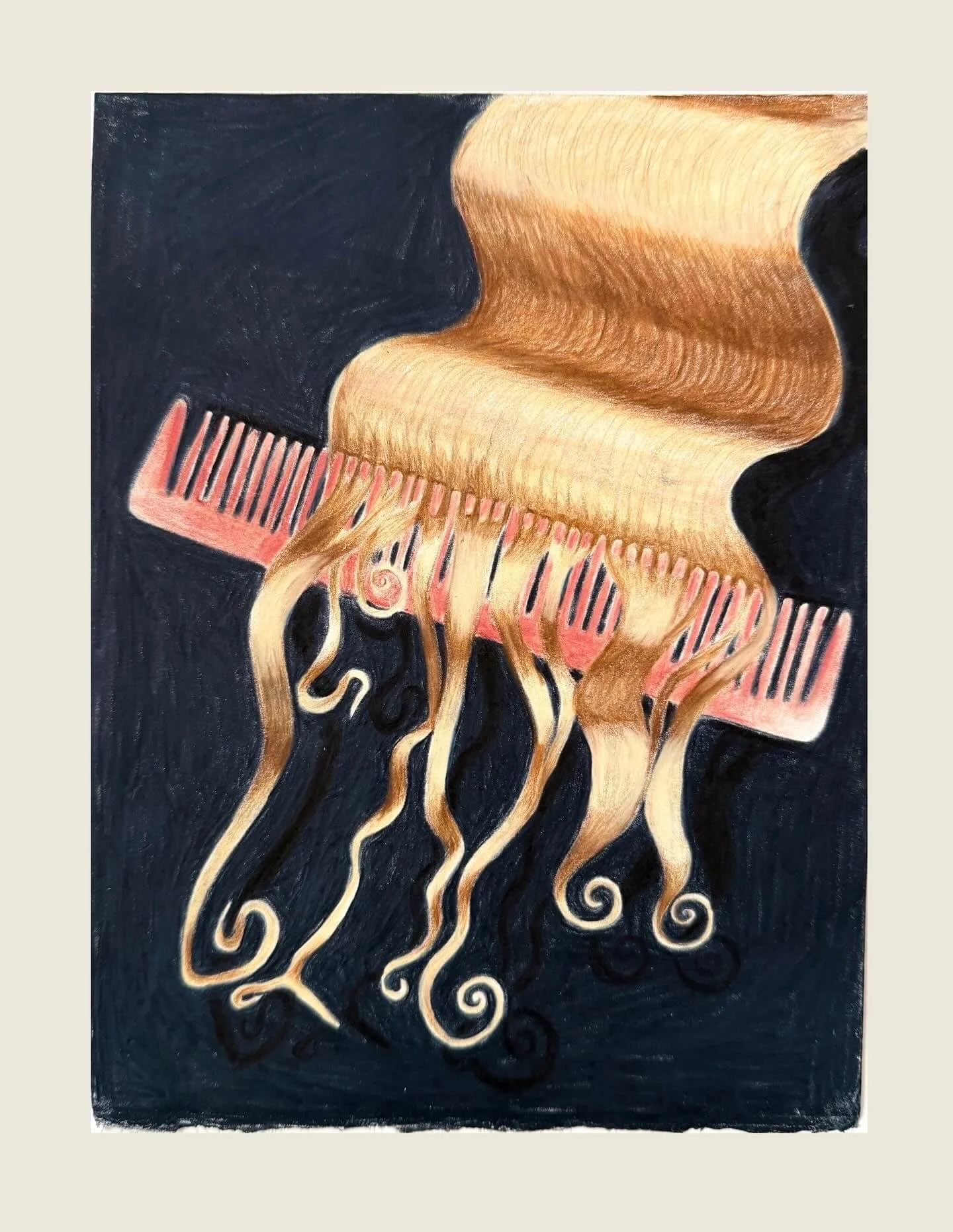

Darcy Whent’s practice delves into the complex ideologies surrounding motherhood, specifically the "dysfunctional responsibilities" often anticipated within the maternal role. Through a lens of personal inquiry and autofiction, she uses painting and drawing to engage with recurring protagonists and motifs. By blending found imagery with personal archives, Darcy constructs narratives that deconstruct the concept of motherhood, revisiting past grief from a present perspective. Her work challenges the rigidity of memory and truth, creating a "universal form of childhood" that—while emotionally true to the artist—replaces literal memory with a fabricated, desired reality. She explores how environments shape behavior, using overwhelming patterns to evoke domesticity, comfort, and the suffocating confinement of being "assigned to our mothers.

Artist Website: www.darcywhent.co.uk

Interview

You describe your practice as "autofiction," noting that the childhood you present in paint is true to you but not necessarily true to the actual memory. How do you navigate that tension between preserving a feeling and fabricating a new narrative?

Autofiction allows me to treat memory less as an archive and more as a material — pliable, unreliable, and emotionally charged. When I paint, I’m not trying to recreate an event as it happened; I’m trying to capture how it felt and how it continues to reverberate in the present. That tension between fact and fabrication becomes a generative space: the act of painting becomes a negotiation between what I remember, what I misremember, and what I need the narrative to become. The resulting images often sit slightly askew from the truth, but they’re emotionally accurate. They preserve an atmosphere, a tone, a psychological residue rather than a literal memory.

Looking back at these events and stories from where I stand now has become an essential part of my process. I’m constantly aware that the way I interpret my childhood — and the narratives I construct around it — is shaped by who I am in the present moment. As I continue to mature, the work shifts with me. What once felt like a fixed memory becomes more fluid, open to reinterpretation, or even contradiction. This reflective distance allows me to see patterns, tensions, and emotional truths that I couldn’t recognize before. The paintings evolve as I do; they absorb the changes in my understanding, my relationships, and the language I use to articulate these experiences. In that sense, the work is never static — it grows, reconfigures, and repositions itself alongside my own development.

Your work utilizes both found imagery and personal archives. How do you select which images to include, and how do they interact to build what you call a "universal form of childhood"?

I pull from personal photographs, family albums, old magazines, illustrated books, and sometimes images that circulate online — things that feel strangely familiar even when I don’t have a direct connection to them. I’m drawn to images that hold a kind of emotional ambiguity, where the gestures or environments feel recognizable but are not tied to a specific, identifiable narrative. When these disparate sources meet in the studio, they begin to flatten into a collective language. By mixing my own history with anonymous or borrowed childhoods, I remove the specificity of identity and allow the viewer to project themselves into the work. The “universal childhood” I’m searching for isn’t idyllic; it’s unstable, tender, and shaped by the invisible structures of family life.

You mention using overwhelming patterns to access feelings of domesticity, comfort, and confinement. Can you tell us more about how you use these visual elements to represent the psychological space of being "assigned to our mothers"?

When I talk about overwhelming pattern in the work, the motif of the shell has become increasingly important. The shell functions as a stand-in for “home” — something protective, familiar, and enclosing. It mirrors the domestic environments I grew up in: decorative, intimate, and seemingly safe. But a shell is also incredibly fragile. It can crack with the slightest pressure, and that brittleness feels symbolic of the instability that often sits beneath the surface of family life.

Patterns — floral wallpapers, quilts, fabrics — carry an immediate sense of domestic intimacy. They’re comforting, nostalgic, and visually decorative, yet they can also feel suffocating when they accumulate or repeat excessively. In my paintings, these patterns swell and sometimes spill into the figure, creating a blurring between environment and body. This reflects how childhood often binds us to our domestic roles before we understand them. The idea of being “assigned to our mothers” speaks to an early, unchosen proximity — a closeness full of love, dependence, and sometimes claustrophobia. By letting patterns engulf or press against the figures, I try to evoke that psychological thickness: the feeling of growing up inside structures that shape us long before we can resist them.

Your statement touches on "dysfunctional responsibilities" and the possibility of inherited behaviors. How do you translate these invisible, often internal social barriers into physical motifs or protagonists within your paintings?

I’m interested in how inherited behaviours and invisible emotional labour show up physically — in posture, gesture, facial expression, or even the tension between figures. Many of the protagonists in my work appear simultaneously childlike and adult, caught in a transitional or ambiguous age. This slippage helps me explore the way we carry childhood responsibilities into adulthood, often without realising it.

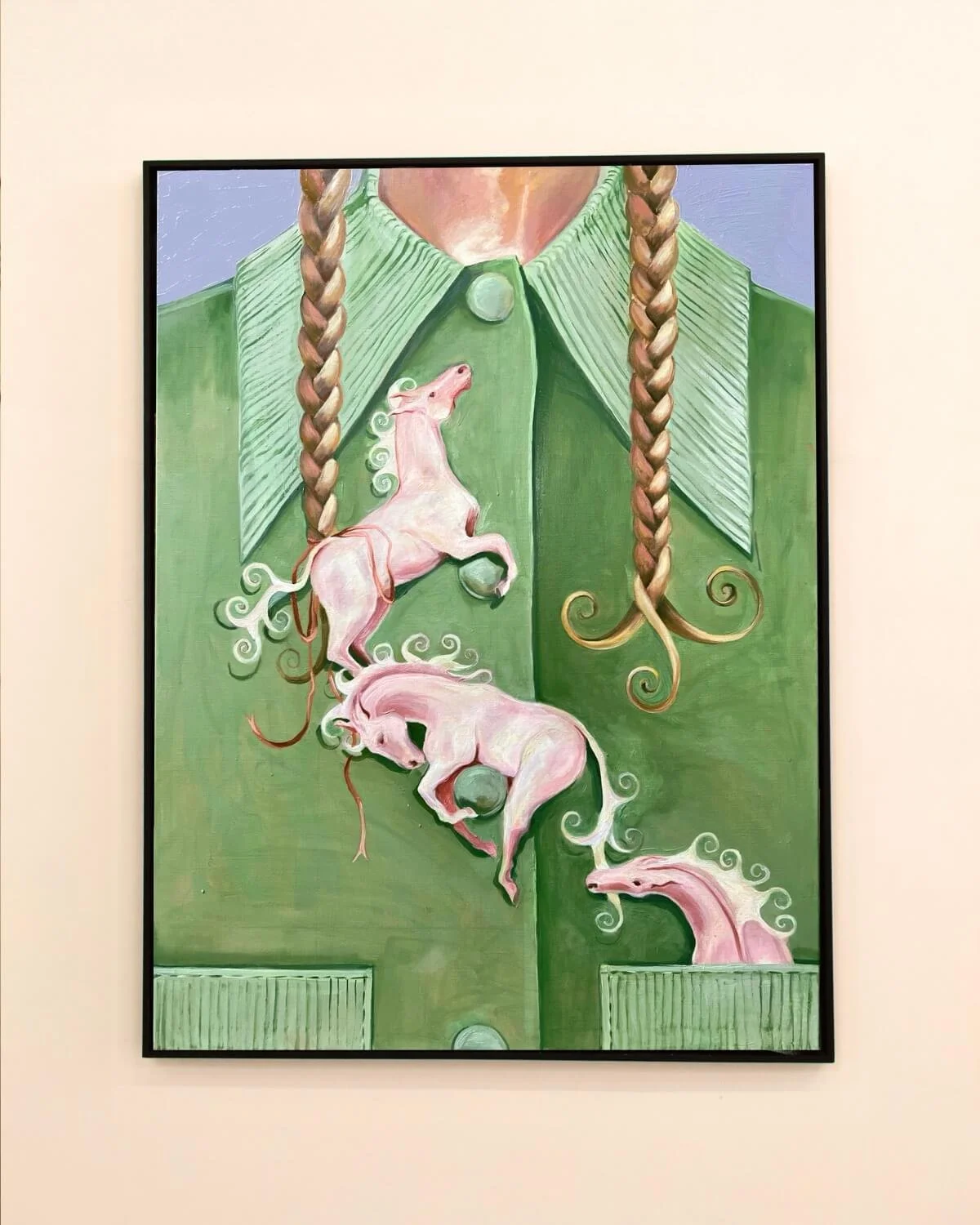

Motifs like leashes, harnesses, bridles, or domestic objects become metaphors for inherited expectations. The characters are often presented mid-gesture, as if reacting to an unseen instruction or resisting a habit they’ve internalised. I think of these images as psychological portraits rather than literal scenes: the barriers appear not as walls but as attachments, loops, repetitions, or frictions in the composition.

You drew a compelling parallel between a child’s development and a domesticated animal adapting to its owner. How does this concept of environmental control influence the composition and boundaries within your work?

That comparison comes from thinking about how children adapt to the emotional climate of their home in the same way animals adjust to the behaviours of their owners. It’s not a perfect analogy, but it helps me visualise the shaping forces at play. In my compositions, boundaries often appear as tight framing, cropped bodies, or enclosed interiors that limit a figure’s movement. Sometimes the figure feels trained, staged, or directed, positioned within patterns or spaces that subtly control them. Other times, the boundaries are internal — figures split, repeat, or fold into themselves as if responding to an unseen authority. The compositions often push the figure towards the edge of the canvas, echoing the pressure to adapt, behave, or contain emotion.

Your forthcoming exhibition is titled Becoming Feral. Does this new body of work represent a departure from that domestication, or perhaps a different reaction to it?

Becoming Feral explores what happens when those domesticated structures begin to crack. It’s less about breaking free entirely and more about imagining a psychological state where learned behaviours slip, mutate, or become unstable. The figures in this series occupy a space between obedience and instinct — between the roles they were taught and the impulses they’re trying to reclaim. The work isn’t rebellious in a straightforward way; it’s more about recognising the animal part of ourselves that has been trained into submission. In that sense, “feral” becomes a metaphor for self-recognition, a way of acknowledging the inherited scripts while also pushing against them. It’s a departure, but a gentle, uneasy one — a kind of soft wildness emerging from within the familiar.

A recurring idea in my work is the notion of becoming feral — a state of slipping out of what is expected, rehearsed, or socially acceptable, and entering a rawer, more instinctive mode of being. I think of this “feral” state not as wildness in the chaotic sense, but as an emotional and psychological shedding: a moment when the self is unguarded, untrained, and alert to its own instincts.

For me, this sense of ferality sits within the liminal space between girlhood and womanhood. It is the phase where rules, roles, and responsibilities begin to press in, yet the body and psyche are still shaped by a kind of untamed interiority. It’s a threshold: you are no longer a child, not yet fully formed as an adult, and it is in this in-between zone that the contradictions of identity come sharply into focus.

Becoming feral is a response to transition. It’s the moment where a young woman pushes back — consciously or unconsciously — against expectation. There is conflict, friction, emotional volatility, but also an emerging agency. The feral self acts out, hides, observes, protects, rages, or retreats. It is a survival instinct as much as it is a transformation.

In my work, figures often inhabit this uneasy, shifting space. They exist in states of tension: tender yet defensive, knowing yet uncertain, poised between vulnerability and defiance. The imagery of animals, particularly those that signify loyalty, danger, or instinct, becomes a way to think about how a person transforms under pressure — how the psychological landscape of girlhood can fracture and reorganise itself in preparation for womanhood.

To “become feral” in this context is not to lose humanity, but to reclaim something instinctive that was always there. It is the body remembering its earliest truths before it was told how to behave. It marks the point where memory and identity collide, where past versions of the self haunt and shape the adult they are becoming.

This liminal zone is uncomfortable, unstable, and fertile. It is where I locate much of my practice.