Thinking and Making: Interview with Metal and Jewellery Artist Layla Lin

Yuanxing (Layla) Lin (b. 1997, Xiamen) is a London-based metal and jewellery artist whose work merges craft, material experimentation and feminist thought. Trained at Central Saint Martins, Birkbeck, and later the Royal College of Art, she develops innovative woven-wire metal techniques shaped by textile logics. Her practice spans cutlery, vessels, jewellery, and material studies, with recent exhibitions in London and Paris.

In Layla Lin’s practice, the tension between the structural rigidity of silversmithing and the fluid, mnemonic cadence of the textile is not merely a technical hybridity but a radical reclamation of material agency. Her work is predicated upon a 'textile logic' applied to a metallurgical substrate.

The process of making involves the meticulous weaving of silver and metal wires, an act that serves as an inherent critique of the 'heroic' tradition of the smith. As Glenn Adamson posits in Thinking Through Craft, the domestic associations of craft often germinate from its repetitive, manual labour; Lin leans into this repetition, utilising hand-weaving to recover the 'irrationality' and emotional labour that the industrialisation of silversmithing sought to excise. In her series Surfacing The Crack, Lin investigates the fragility of silver, a material bound to notions of permanence and decorative prestige. By interlacing and forging delicate wires into skeletal forms, she creates objects that are, in her words, ‘strengthened, stretched, and sometimes broken.’ This preoccupation with the fracture echoes Rozsika Parker’s foundational thesis in The Subversive Stitch, which argues that the very domestic crafts used to enforce feminine social codes—needlework, weaving, embroidery—contain the latent power to subvert them. Lin’s approach does not merely challenge the functional authority of the object; they expose the vulnerability beneath, where the ability to melt, weld, and reform material is a radical act of self-collection.

By stripping the silver object to its woven skeleton, Lin confronts the tenuous correlation of value and worth that has historically marginalised domestic craft. Her work demands that the viewer confront the aesthetics of endurance and the invisible labour concealed behind the polished facade of the ornament. Layla Lin represents a new vanguard of artists who refuse the 'separate spheres' ideology of material culture, offering instead a critique of how we assign value to objects and, by extension, to the bodies that produce them.

What initially sparked your interest in metalwork and jewelry?

What inspires me most in metalwork and jewellery is the unique experimental nature of the field, and the intensity of the narratives that can emerge from the making process itself. In this genre, the body becomes an active site for artistic expression. It creates a kind of miniature theatre while also serving as a branching bridge—one that allows essential contemporary reflections on society to manifest through both the functional and philosophical dimensions of an object.

My understanding of applied arts gradually formed during my jewellery studies and deepened as I continued working in the field. I’ve also come to feel that the rise of applied arts represents, in a way, the rise of amateur and vernacular craft practices—challenging the former dominance of fine art over cultural discourse.

Ultimately, I was drawn toward the study of specialised technical craft. Encountering a wide range of ethnic and studio-based practices, as well as the contributions of women in these traditions, made me more aware of how contemporary jewellery—much like textile and other handcraft techniques—bears witness to the revolutions and progress of marginalised groups, whether defined by gender or race. All of these continue to resonate deeply with me.

Identity Necklace, 2023, Silver and Gold.

How would you describe your creative process? Do you begin with sketches and extensive planning or work more intuitively?

This is a very important aspect of my practice. I often feel anxious when sketching ideas, as I am not always confident that I can fully realise what I imagine. As a result, my current body of work has largely been developed intuitively and through extensive material experimentation. However, as I have made significant technical improvements—especially after resolving several major issues through repeated practice—I have become increasingly confident. I now find myself more willing to sketch ideas in advance.

Another key influence has been my experience of making the silver cutlery set this year. It was a challenge I set for myself: not only to hand-weave the material and form it into familiar shapes, but also to apply the knowledge and inspiration I have accumulated throughout my practice. Initially, I planned to make the pieces very large and to combine thick and thin gauges of silver to create visual contrast. I produced sketches and samples, through which I began to recognise the project’s immense potential. The collection ultimately became three pieces of cutlery, each measuring 25 cm in length—an unusual scale for such objects.

It was at this stage that I realized the final pieces were very close to my original sketches, yet subtly different from what I had expected, or from what I had imagined would be “great.” This led me to recognise that I am moving away from relying solely on intuition and entering a new phase of my practice—one that integrates both design and craft.

Woven Cutlery, 2025, Silver.

What do you love most about working in metal and what about it is the most challenging aspect?

I have carried a question with me for a long time: why is jewellery design so often centred on working with metal? For example, when I studied in Germany and later in Japan last year, there was a clear distinction between the categorisations of “jewellery making” and “metalsmithing/silversmithing.” The former refers primarily to design-led practice, in which the skills acquired serve the goal of producing an outstanding final outcome. The latter refers to a different educational model, where apprentices spend countless hours developing their handcraft skills in metal, often focusing intensively on a single technique.

During my years at Central Saint Martins, however, we were taught to focus equally on thinking and making. While “thinking” encouraged me to step outside established frameworks, “making” compelled me to develop a deep and embodied knowledge of metal. I experienced a long period of confusion within this tension. Eventually, I realised that focusing on silversmithing gives me the greatest agency as an artist. I am drawn to the way metal continues to hold vitality in the creation of new forms after so many centuries, and to how it represents a fundamental element in the construction of human society, carrying the weight of time and history.

My focus on, and understanding of, metal became fully formed during my MA studies, both through theoretical engagement and studio practice. I came to the decision that metal—particularly silver—supports not only experimentation but also deeper artistic research. I believe it is essential for an artist to identify their own material through which to explore specific crafts. For me, uniqueness and craftsmanship are the most important values within this process.

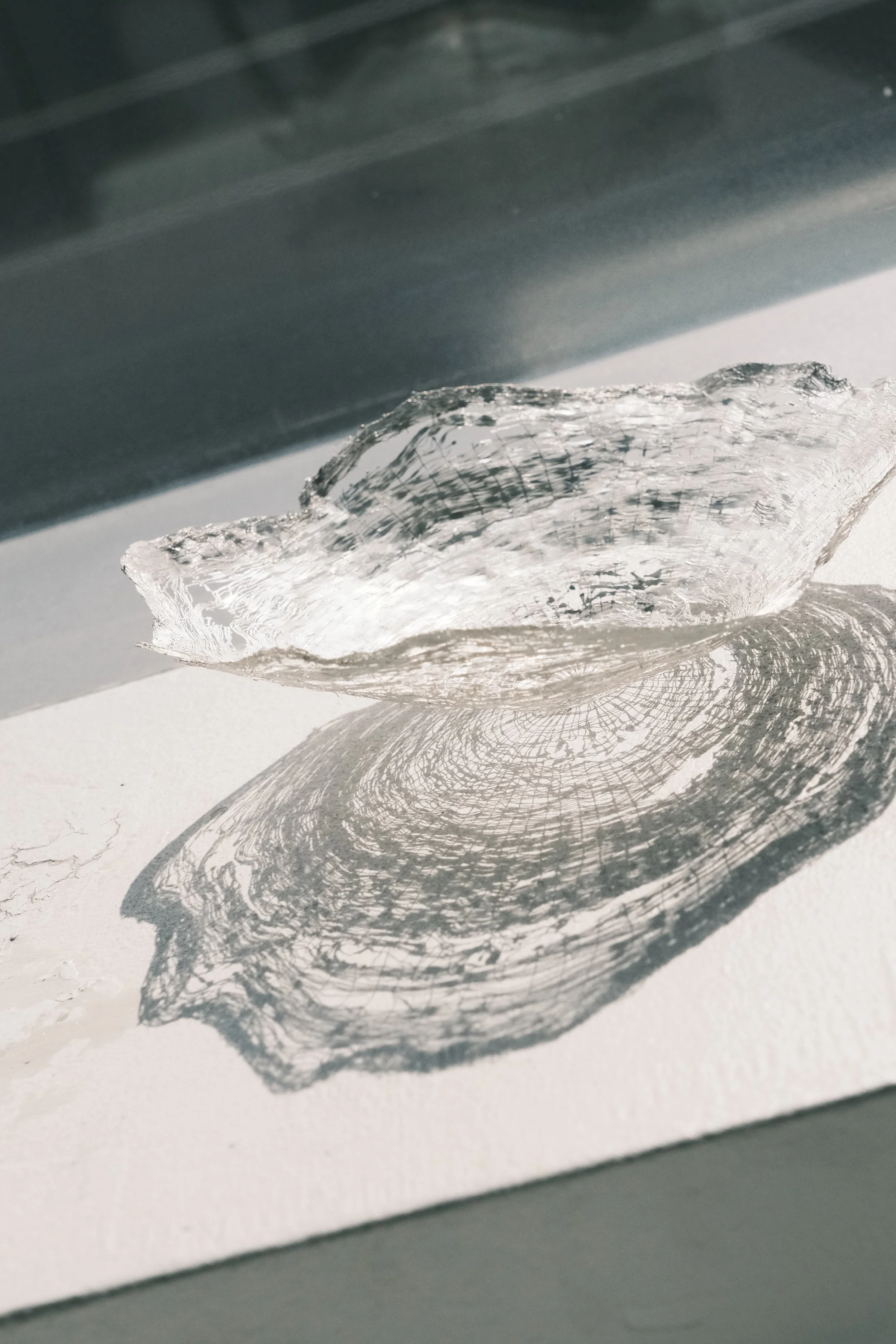

Surfacing the Crack #2.

Your work aims to bridge craft with feminist discourse. Can you tell us about how a series or specific work allows you to explore these themes?

Enabling my work to articulate feminist themes is both a goal and an ongoing challenge within my practice. I began developing my current body of work after completing my first Master’s degree in Cultural Studies, where I became deeply engaged with feminist theory and its relationship to applied arts such as jewellery and textiles. This interest has driven me to search for a deeper sense of purpose within my practice and has helped me to articulate why I am particularly drawn to multidisciplinary forms of art.

Female artists such as Ruth Asawa, Meret Oppenheim, and Louise Bourgeois have been especially influential for me. Their practices range from small-scale, everyday objects to works that are spatially and conceptually expansive. For me, this reflects the limitless potential of applied arts—their ability to extend from the minimal and intimate to the ambitious and seemingly impossible.

Feminism, on the other hand, holds its vitality in processes of reconstruction and transcendence, rooted in a broad spectrum of female knowledge and lived experience. To work through feminism is to reinterpret the ordinary. This way of thinking guides my movement from feminist theory into weaving, and then back into the reconstruction of weaving, often hybridised with metalwork. These aesthetic considerations and practical methodologies have allowed me to bridge theory and practice, integrating my work with my own embodied experience and using it as a vehicle for communication.

Surfacing the Crack #3, 2024, Silver.

Congratulations on your exhibitions this year! What would you say were the highlights in 2025 and what are you working towards next?

Standing at the beginning of 2026, I feel that 2025 marked the departure point of a new journey for me. The highlights of the year were undoubtedly the exhibitions—particularly one during London Craft Week, where I received a commission from the designer of a Michelin-starred restaurant in Copenhagen—as well as several meaningful collaborations with friends. Through these experiences, I feel that my future is gradually taking shape, or at least becoming clearer than it was before.

In the next stage of my practice, I aim to work as a full-time artist based in London, while also undertaking residencies both within and beyond the UK. I am keenly aware that my work still requires further challenge and development, both technically and theoretically, and I see residency programmes as essential spaces for growth, experimentation, and critical reflection.

Novo Showroom, 2025.

Critical Review by Dot Zhihan Jia

Dot Zhihan Jia is Curator (Studios and Residencies) at Studio Voltaire, where her work facilitates artist professional development and cross-regional exchange. Previously at Tate Modern and esea contemporary, she is a board member of Saloon London, a member of the Feminist Duration Reading Group, and editor of the bilingual food magazine chán. She is the recipient of the 2021 PSA Emerging Curator Award, and has collaborated on projects with institutions including ICA London, Shanghai Power Station of Art, and Goldsmiths CCA. She currently teaches at Goldsmiths and Chelsea College of Arts.

Interview by Alicia Puig

5 January 2026