Inside Verónica Gómez’s Fantastical Worlds Where Beauty and Horror Coexist

Verónica Gómez is a painter, writer, and educator based in Buenos Aires. She holds a degree in Visual Art from Argentina’s National University of the Arts and has exhibited her work across Latin America, Europe, and Asia. Her paintings, striking for their detail and theatricality, depict fantastical, unsettling scenes inhabited by ghostly girls, anthropomorphized animals, masked figures, and surreal objects. Rich in symbolism and emotional tension, these images invite interpretation. Viewers often recognize personal or political truths in Gómez’s allegories—reflections on memory, vulnerability, political absurdity, and social climate.

In this interview, the artist reflects on her early influences, her material process, and the tension between beauty and horror in her work. She speaks about the artist’s role in times of crisis and the importance of staying connected to one’s creative instincts.

Artist Website: https://veronica-gomez.com.ar/en/veronica-gomez-projects/

Social Media: https://www.instagram.com/veronicainesgomez1/

Niña Pomelo reads the fate (2025). Oil on canvas. 14,6 x 11 in.

You were born and educated in Buenos Aires, emerging as an artist in Argentina’s dynamic early-2000s art scene. What were some of the pivotal influences or formative experiences that shaped your path early on? Were your artistic pursuits encouraged at home, and who or what helped nourish your practice as a young artist?

My father painted as a child; my grandmother used to take him to study with a teacher who made him copy reproductions of Baroque paintings—still lifes, landscapes—something very usual at that time. As an adult, he stopped painting and became a scientist, but I inherited his box of oil paints and his palette. When I was 11, I asked to study at an art workshop in the suburbs of Buenos Aires, a place that was both bohemian and academic. There was no connection in my family to contemporary art, let alone to the gallery or art fairs. But I do remember my mother taking me to the Museum of Fine Arts and the Museum of Decorative Arts. Those experiences marked me deeply. At home, we collected The Geniuses of Painting, published by Sarpe, the Spanish publishing house, and I would go crazy looking at them, over and over again; they mesmerized me. I was an extremely shy child. I remember feeling a great desire to hide. And painting was a form of communication that didn't need words. And it gave me a window to other worlds that— I now understand—were easier for me than the real one. When I graduated from high school, it was quite clear to me that I was going to study Fine Arts.

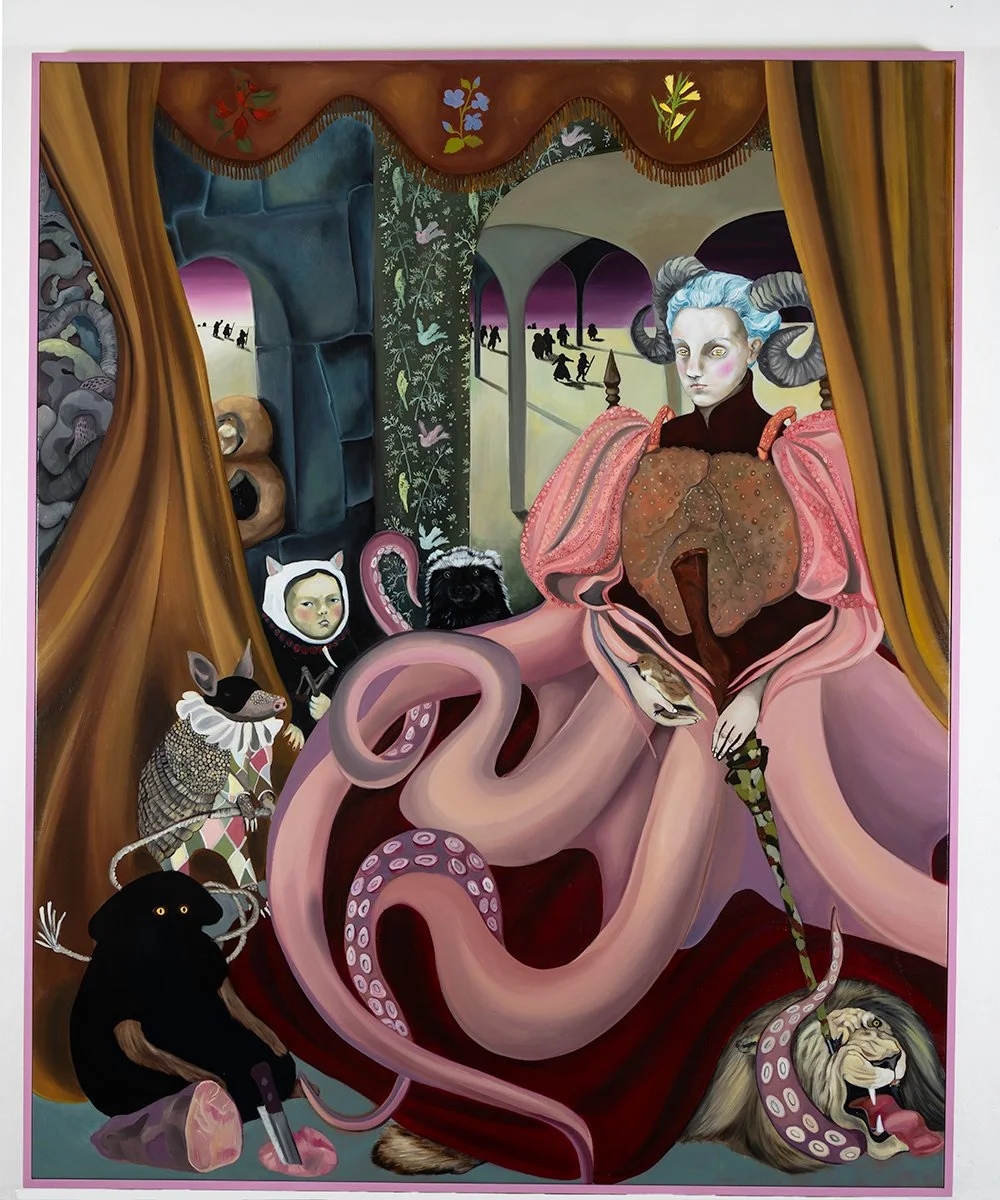

Queen Pulp gathers her army of Lilliputians (2025). Oil on canvas. 76,4 x 62,2 in.

Your work is allegorical, filled with symbolism, surreal characters, and layered narratives that invite viewers to actively decipher the meaning behind each image. When constructing these visual allegories, do you start with specific symbols and ideas in mind, or does the meaning emerge more intuitively as you paint? How do literature and folklore, history and current events, or your own experiences inspire and shape the imaginative worlds you create on canvas?

The construction of these visual allegories begins in dissimilar ways, but they all have something in common: they arise from an irruption that becomes inescapable for me. An element that I perceive as weird and significant, that captures my attention to such an extent that I say to myself, “I must make a painting of this.” This irruption can occur in the supermarket, observing a pumpkin with singular shapes; during a psychoanalysis session, that “eureka” moment that tugs at all your experiences; looking at a face in a painting from another era that I recognize as strangely familiar; an unusual animal that appears on Instagram; the textures of certain materials like marble or skin; some piece of information that appears during an Akashic Records reading; a detail in a story by Fleur Jaeggy or Aurora Venturini. In that sense, my work is quite surrealist, as exemplified by this phrase from the Comte de Lautréamont, so foundational to the movement: “Beautiful as the chance encounter of an umbrella and a sewing machine on a dissecting table.” Except I don't believe it's fortuitous; I believe more in the Chinese concept of yuanfen, a predestined connection. I'm also hypersensitive to contexts, which is why residencies (in Finland, in China, or when I moved out of my studio to the city center) immediately poured into my paintings, contributing not only with new elements and narratives but also atmosphere.

Mother Owl (2025). Oil on canvas. 42 x 28 in.

Many of your works use fantasy to comment on political and social realities. What role do you believe artists can play in responding to moments of upheaval or injustice? When you use fantasy or allegory to engage with current events, what do you hope viewers take away from it?

I believe that artists can use their technical and metaphorical resources to bear witness to a political moment that is becoming suffocating and distressing. There is a long tradition in painting of this kind, in different parts of the world and throughout history. In Argentina, to give just a couple of examples, we had Cándido López, who painted the War of the Triple Alliance, and Antonio Berni, who created some heartbreakingly powerful works about the dictatorship (among many other artists). My experience creating paintings that allude to the current Argentine political context—being governed by an extreme right wing with decidedly farcical characteristics—is that Argentinians suffering under this government felt relieved and grateful upon seeing the works. It happens that when we put something into an image, even if that image is horrific, we draw it off from ourselves, and that's where empathy begins. “You see the same thing I do, and you were able to paint it, thank you!” That's what they tell you. And something wonderful happens: that image is no longer yours, that image serves a purpose, in the same way that a song serves and accompanies it.

Ping Guo calms the Lion (2025). Oil on canvas. 14,6 x 11 in.

Your paintings are rich not only in narrative but also in form, often full of ornamental details and embellished with fabric and embossed frames. Could you walk us through your creative process from initial concept to final execution? What guides your decisions about materials, composition, and details that make your work so distinctive?

I believe my creative process is guided by the collage method. One element leads to another. And that's how the scene, the characters, and the stories are built. I adore ornamentation; it's a very effective way to catch the eye and fill voids. Ornamentation is something very profound, existential. Gombrich already explained it in his wonderful book, The Sense of Order. And I'm fascinated by its logic, sometimes quite whimsical. There's a kind of delirium there, a fantasy that expands across surfaces and allows one to travel. In China, I was driven mad because there, curves, twists and turns, and multiplication reach unimaginable levels. Wherever I go, it's something I pay close attention to, and it appears in my paintings and in the canvases I choose for the frames. I'm interested in the painting being, in some way, precious. Even if its content is sinister, melancholic, or tender, I don't consider a painting finished until I deem it “precious.” This has to do with value; precious is something abundant in value, highly esteemed. Ornamentation is a way of making something precious. It has to do with dedication, work, and being loving towards what you're doing. To adorn is to caress again, to want a little more. Of course, there's a poetics of emptiness, but I'm on the side of horror vacui, haha.

The Proposal (2025). Oil on canvas. 35,4 x 31,5 in.

You’ve participated in art residencies across Europe, Asia, and Latin America and exhibited internationally. How have these cross-cultural encounters impacted your practice? Do you notice differences in how your work is received in other cultural contexts?

Artist residencies are a great opportunity to draw inspiration from different influences. On the one hand, you enter a state of heightened sensitivity; stimuli emerge in the new context like guiding lights. It's a state of great openness and joy, where the senses are fully awake, discovering, collecting, flowing in a creative dispersion. However, on the other hand, it's a state of intense concentration, of retreating to the temporary studio to further investigate what you've gathered, observing how it modifies or connects with what you brought with you. Because my work is very narrative, it generally connects well with the people; very intimate conversations sometimes take place. I've never felt that cultural differences are a barrier to connection. What I've been able to verify, and what gives me great satisfaction, is that humor and tenderness, so present in my work, transcend cultural differences.

Mother Jellyfish (2025). Oil on canvas. 14,6 x 13,4 in.

In addition to being a visual artist, you are also a writer and an educator. How have these parallel roles informed your work as an artist?

Being a teacher and an artist are, for me, two sides of the same coin. It’s a dialectical relationship. One wouldn’t exist without the other. It's an incredibly powerful economic and psychological alliance for me. But be aware that you have to differentiate the roles; that's the most beautiful thing, because it allows for flexibility, it’s an exercise in crossing thresholds, in expanding yourself. When I'm a teacher, I'm the artist at the service of someone else's world; when I'm an artist, I bring influences from my experiences into my own works. As for writing, I've always developed it in relation to the visual arts; anyway, someday I'd like to publish fiction. But in any case, I recognize reading as an important influence on my paintings.

The Virgin of the Lake (2025). Oil on canvas. 15 x 11 in.

What advice or insight would you offer to emerging artists who are still discovering their creative voice and vision? Are there lessons or insights you’ve returned to throughout your career that might resonate with artists navigating uncertainty?

My advice would be that they remain in close contact with that which initially led them to paint, draw, and bring objects and images into this world. It’s important not to lose the connection to their art despite financial issues. There's a song by Silvio Rodríguez that says something like: “You must embrace the time of trying, you must embrace the hour that never shines, and if not, don't expect to touch what is certain, only love breeds wonder.” I think that's the way it is.

Are there any upcoming projects, exhibitions, or collaborations you’d like to share with our readers?

Until February, I'm participating in a group exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Buenos Aires, curated by Raúl Flores, which explores the relationship between the visual arts and theater. In March of next year, I'll be participating in the exhibition Dark Continent, curated by Leandro Martínez Depietri, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Buenos Aires, focusing on female artists and their connection to Surrealism. And in the second half of the year, I'll be part of an exhibition at the Museum of Oriental Art with the Argentine artist Lula Mari, which will explore my experience of my residency in Beijing.