Exploring Life, Death, and Humor: An Interview with Artist Andreea Alunei

Andreea Alunei is a Romanian multidisciplinary artist based in Bloomington, IN. She currently teaches as a Visiting Assistant Professor at the Eskenazi School of Art, Architecture + Design at Indiana University, where she also earned her MFA. Her background in both psychology and visual art informs her layered, symbolic painting practice.

Alunei’s small-scale works explore themes of motherhood, mortality, and spiritual uncertainty, using vivid color and surreal humor. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, including at Field Projects Gallery (NYC), Manifest Gallery (Cincinnati), and New House Art Space (UK). In 2024, she was named one of ten standout North American visual artists by curator Hettie Judah through the Acts of Creation competition.

Artist Statement

My work explores existential uncertainties through the intertwined experiences of life entering and leaving the body—the birth of my daughter and the death of my mother. These events, and the maternal bond they represent, shape my ongoing investigation of birth, death, spirituality, cultural identity, and motherhood.

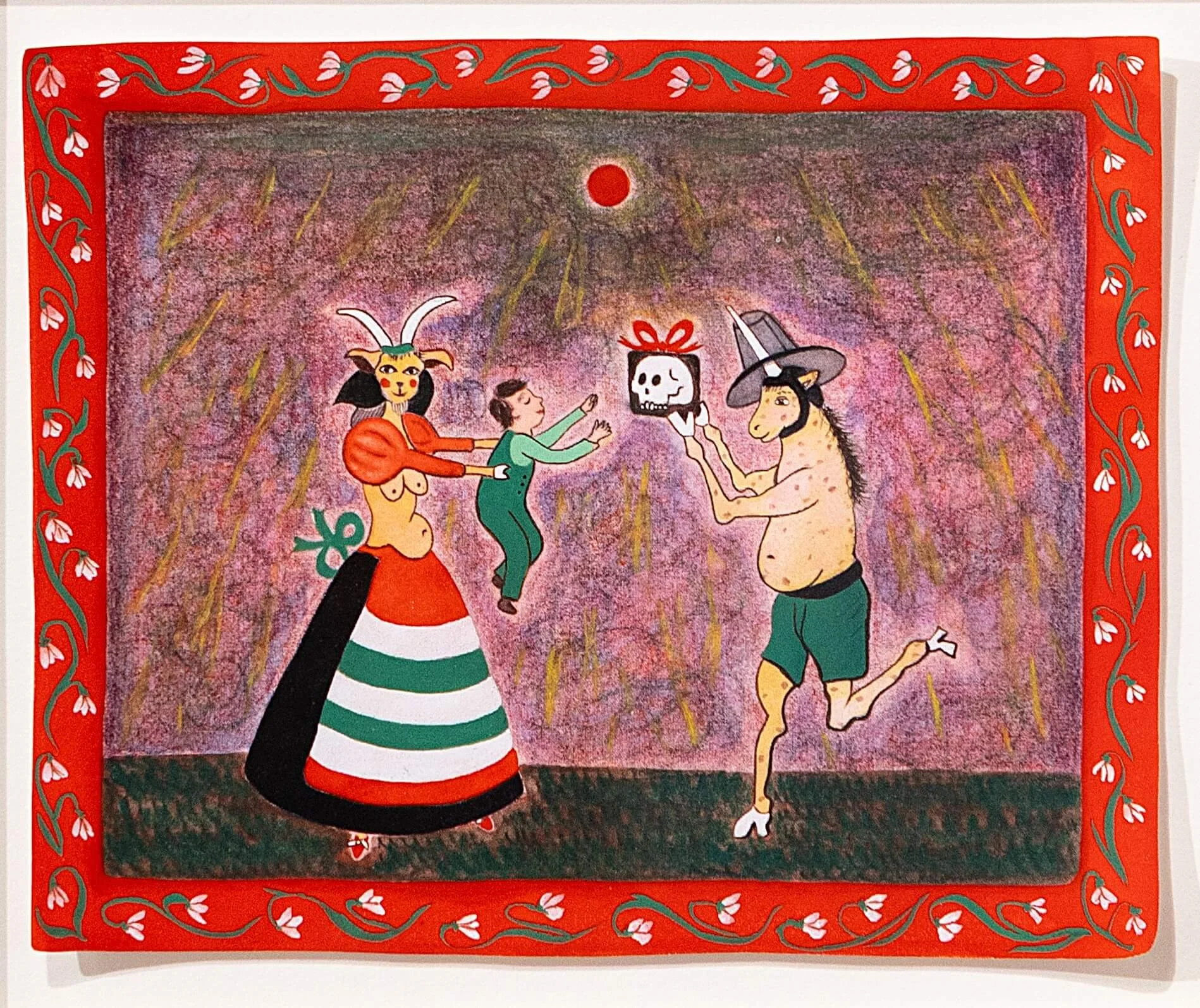

By blending the observable with the imaginary, I create a personal mythology in small-scale, layered paintings. Using mixed media on silk, I build tactile, luminous surfaces that reflect fragility, impermanence, and spiritual longing. Inspired by medieval illuminated manuscripts and children’s illustrations, I focus on symbolic meaning over anatomical accuracy. Recurring motifs—halos, goats, unicorns, mice, and children—populate a whimsical, surreal world where roles and realities shift.

I approach painting with apprehension and reverence, treating the process almost superstitiously. Moving fear onto the surface becomes an act of courage and a way to transform vulnerability. Rooted in grief but resisting solemnity, my work uses humor and playfulness to create space for confronting fear with lightness—offering perspective on mortality and life’s absurdity.

Artist Website: www.andreea-alunei.com

Interview

Your paintings weave together themes of motherhood, loss, and renewal. How did the intertwined experiences of your mother’s passing and your daughter’s birth begin to shape your visual language?

Those two experiences will always live side by side in me: the death of my mother and the birth of my daughter. When my mother died, I was shaken to my core. Mortality became unavoidable, something I could no longer look away from. That awareness stayed with me, insistent and unresolved. It became a kind of obsession that might never leave me. Then my daughter was born, and suddenly life and death were no longer abstract; they were physical truths I carried in my own body. It was terrifying and strangely powerful. Painting became a way to hold both grief and wonder without collapsing into either, a way of expressing power and birthing things into existence again and again.

I do not belong to any single belief system, so I turned to painting to build a kind of spiritual framework for myself. It is a way to live with questions that have no clear answers. I draw from myth, occult symbols, religious art and texts across cultures, folklore, and even meme culture, taking what resonates and leaving what does not. I often joke that I have built a Frankenstein’s monster of ideas about life and death. I know it is a construction, fragile and flawed, yet it gives me a place to return to when I face the unanswerable or when I am simply trying to make sense of ordinary human messiness.

I paint small and colorful, in ways that feel both playful and devotional. It is an unusual combination: a meditative practice that also makes room for scrabbling with crayons. That tension between control and surrender, reverence and irreverence, discipline and play, feels closest to what painting is for me. It is a space where I can think through the experiences of mothering and being mothered, and where seriousness and absurdity can coexist without cancelling each other out. Thinking about death inevitably makes me aware of life’s absurdity, and that awareness seeps into the work. My practice is serious, but it also laughs at itself, and that’s probably the truest part of it.

Many of your works draw from both medieval illuminated manuscripts and children’s illustrations. What draws you to these influences, and how do they inform the symbolic worlds you create?

It honestly just happened through love and exposure. I have always been drawn to medieval art because it is both funny and profound. I can’t get over the fact that artists abandoned perspective for centuries because it simply wasn’t what mattered. They were more interested in meaning than realism, and I follow in their footsteps. Also, who doesn’t like a medieval cat? Those paintings were trying to make sense of the same big questions I am still asking, though within a narrow Christian framework. They were also a way to communicate complex ideas to people who could not read, which is exactly what good children’s illustrations do. When they are done well, they carry the story entirely, and the words become almost secondary.

As a child growing up in Romania, I did not have much access to art. The only images that surrounded me were religious icons and illustrations made for children, mostly in books or on television. Funnily enough, those two visual languages, one sacred and one naive, seem to have fused into my artistic DNA. Both use simplicity to point toward something larger, and both are trying in their own ways to teach us how to see and understand the world around us. They are meant to grab your attention and hold you there, to make you believe in something. They are made for consumption, accessible, and deeply embedded in people’s everyday lives and imaginations, probably far more influential than fine art can ever hope to be.

That is what fascinates me most. Both forms depend on the same kind of visual tension. They move between simplicity and excess, flatness and ornament, clarity and saturation. They build entire worlds through specificity, where every object or pattern carries meaning. The outfit of a saint or the shape of a cartoon character’s body can tell you everything you need to know about who they are. That kind of visual shorthand feels timeless to me, and it continues to guide how I approach painting today.

I also like to break the rules of painting and drawing, often the same ones I teach during the day. My partner likes to tease me that I have oppositional defiance disorder, which I will deny until the day I die.

Humor and playfulness show up in your work even when exploring grief and mortality. How do you approach this balance between lightness and solemnity?

It probably goes back to my training in psychology. Humor is a coping mechanism I hold close. I remember a college psychology professor calling it “the most sophisticated coping mechanism,” and I think he was right. Humor brings me back to the present. It creates just enough distance between me and fear to start questioning it. To make a joke, you have to step back and look at things from a different angle, which is a valuable skill.

When people grapple with big metaphysical questions about life and death, they often swing toward extremes: either stiff and overly philosophical, or dark and emotional. I am not really interested in either. I want my work to bring a kind of lightness to those conversations instead. Humor lets me sit with difficult truths without collapsing under their weight.

I think of humor as a kind of spell, like the “Riddikulus” charm in Harry Potter, where you confront a shape-shifting fear by laughing at it. Once you laugh, the fear loses its power. In painting, that laughter becomes visual. It softens the terror of mortality and replaces it with curiosity, absurdity, and tenderness. I am not the first to walk that line between tragedy and humor. Artists from Dada to Surrealism used laughter to face the absurdity of existence, and many contemporary artists do it too. I love how Madeline Donahue uses humor to talk about motherhood, or how Tina Newberry inserts herself into historic paintings as a kind of gentle self-parody. I think I might be a shy, closeted comedian at heart—I watch a lot of stand-up.

In my own practice, humor and play are inseparable from painting itself. I think my paintings turn out best when they feel unguarded and immediate. Approaching painting as play keeps me honest. It is an antidote to overthinking and a way to access intuition that goes beyond the logic of the mind. Humor keeps me from taking myself, my work, and life too seriously, and that feels essential.

Recurring motifs like halos, goats, unicorns, and children create a surreal cast of characters in your paintings. Do these figures hold personal meaning for you, or do you see them more as archetypes?

It’s both. When I first started painting, I thought of my work as autobiographical, as many women artists have. But over time it has moved closer to autofiction. That shift gives me room to start from personal experience but stretch it into something less literal and more imaginative. Cindy Sherman comes to mind, but also Kiki Smith, who blends myth, memory, and the body into something symbolic and open-ended.

In my paintings I move from figuration into symbolism, using recurring motifs that carry emotional weight. Over time I have developed a cast of characters that act as stand-ins for myself, for people in my life, and for broader ideas. But they are never fixed; they shift roles and challenge their positions among one another, in relation to the viewer, and even in relation to me. Sometimes I paint from the perspective of the goat, other times from that of the child. It is all very fluid.

I work with a large, constantly shifting bank of symbols, some personal, others borrowed from religious and occult imagery, and many that simply arrive and stay. Certain symbols reappear because they hold emotional charge. The goat and the unicorn are central. The unicorn carries Christian associations of purity, innocence, and sacrifice, while the goat is tied to occult symbolism and ideas of temptation, vitality, and power. They mirror and challenge each other, representing a kind of moral ambiguity, the feminine and the masculine, good and evil. The child often stands at the center of the story, navigating and learning about this strange world. Other motifs return again and again: snakes, skeletons, birds, flowers, halos, masks, and more.

These images form my private cosmology, but they are also meant to be open to the viewer’s imagination and interpretation. I like that a painting can hold personal mythology and collective archetype at once. Meaning shifts depending on where you stand, and I like it that way.

You’ve written about painting as an almost superstitious act, a way of transforming fear into courage. Can you share what that process feels like in the studio?

I think growing up in Romania made me superstitious against my will. It runs down the matriline. I grew up with my grandmother and my mother rubbing my temples and whispering spells to heal my deochi, which is basically when someone looks at you the wrong way or with the evil eye.

Somehow I got it in my head that if I paint something, it can’t happen. So I often paint what I fear as a way to dispel it. It’s a bit masochistic, but staring fear in the face tends to shrink it. Taking the fear out of my mind and into a painting is an act of courage and a resolution to be free. Once it’s on the surface in front of me, I can see that the monster is of my own making. It becomes an image, not a threat, and in that recognition there’s freedom. Painting, for me, is both an act of courage and a way of thinking. I paint to make sense of the world, to turn anxiety into power. There’s often an undertone of fear in my work, but that’s not the destination. I let those feelings bleed into the painting as they must, while staying mindful not to simply add more darkness to the world. Instead, I use painting to change my own mind about things, to question my assumptions and conclusions about reality, and to laugh at my fears a little.

To be able to accommodate this, painting in the studio has taken on the rhythm of ritual. I tidy my space obsessively, light candles, make tea, read poetry from mystics and philosophers, and try to quiet my mind. My studio needs to feel safe, intimate, and to an extent sacred—a place where something beyond logic can enter.

At the heart of all this is becoming friends with not knowing. I don’t know why we are born, why we die, or what any of this means. I don’t think anyone does. But I’ve learned there is value in sitting with that uncertainty instead of trying to solve it. Descartes said, “I think, therefore I am.” I think he overvalued thinking. I don’t know, therefore I paint.

What do you hope viewers carry with them after experiencing your paintings in person?

That’s a hard question. Maybe relief. I hope viewers feel seen and understood in some strange way. Like they are encountering something unfamiliar that somehow feels intimate, the way meeting a new friend whom you feel like you've known forever. That might be a lot to ask of a painting, but I think art, at its core, is a call to intimacy with the world. It is so revealing. I try to hold myself to a standard of brutal honesty, and I hope that honesty creates resonance. I never know exactly what form that takes—maybe laughter, maybe discomfort, maybe stillness—but connection through shared humanity is always the hope. And I do like walking the line between making people laugh and making them a little uneasy. It's the game I play with myself in the studio, too.

Are there any upcoming projects, exhibitions, or collaborations you are especially excited to share with us?

Yes, I am preparing Saints of Unknowing, a solo exhibition opening in January 2026 at the Waldron Arts Center in Bloomington, IN. The show began as a series of invented saints, protective figures responding to fear and uncertainty, rooted in religious iconography, particularly Orthodox imagery and my Romanian heritage. But as the work evolved, I realized my saints are not flawless protectors, figures we revere but never resemble. I start from another premise: that we are all saints. Sanctity is not perfection but potential, sometimes near to the surface, sometimes impossibly remote. Saints of Unknowing inhabits the threshold before sanctity is realized, the human state of not yet knowing. It is a space where what lies within us also moves outward, and our struggles, while urgent, become fleeting when seen from a wider, more cosmic scale.

Beyond that, I am developing several long-term projects that I hope to bring to life when time and funding allow. One is an artist’s book narrated by children who tell the stories of their lives with humor, candor, and an almost absurd honesty. They make you fall in love with them as they speak, and then they bluntly narrate the stories of their own deaths. Inspired by the Merry Cemetery in Romania, it weaves together tenderness, folklore, and the universality of loss. Another ongoing thread, Through Glass Darkly, explores nudity, censorship, illusion, and the politics of looking through layered glass within my existing visual language. These are literal stacked sheets of glass and cutout garments that reveal what lies beneath the surface while questioning what it means to look.

I am also experimenting with large-scale silk prints of my smaller works and constructions that move beyond the frame. I am curious about how shifts in scale might alter both the way humor lands and the sense of intimacy that usually anchors my work.