Zorg's Visual Poetry: Rethinking Identity in a Diverse World

In today's art world, where words like “hybridity” and “cultural collision” are used almost reflexively, it’s rare to encounter an artist who truly questions what those ideas mean. Yet Zorg (Yifan Jing), a London-based artist and Goldsmiths graduate, manages to do exactly that. His work probes the fragile layers of meaning and asks: what kind of visual language can still speak in a world where so many symbols have already been emptied out?

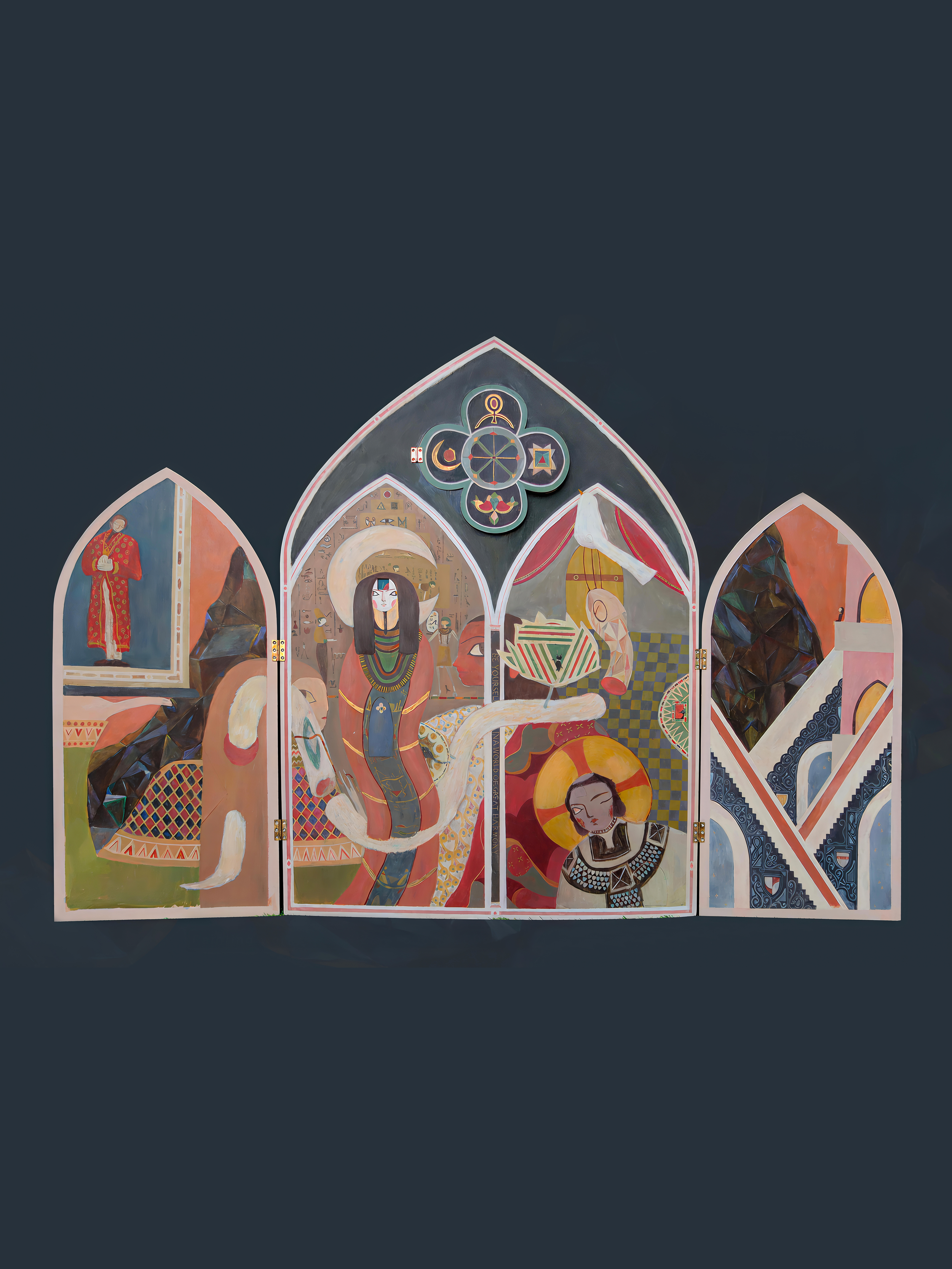

Clover 2024

Zorg’s practice grows from the intersections of different cultures and belief systems—a living texture shaped by movement and encounter. His recent exhibition at Hackney Gallery placed this question at its center. The project draws on his years in East London, a place where Asian, Arab, African, and European communities share the same streets. This dense mix of cultures has quietly shaped how he thinks about belonging and visual language.

Building on the spirit of relational aesthetics, Zorg treats community not as a set of motifs but as a field of living relationships. In the streets of East London, Buddhist totems, Egyptian hieroglyphs, Islamic patterns, and Christian icons appear side by side—in shop windows, murals, and textiles—forming an accidental archive of coexistence. These visual encounters, mundane yet charged, become the ground from which his practice grows.

Zorg’s position in this landscape is never fixed. Sometimes he watches; sometimes he participates. This shifting stance echoes the ethics of artistic ethnography—being present without claiming ownership, translating without appropriating. Rather than trying to resolve the contradictions between observation and empathy, he keeps the alive. Tension, for him, becomes a form of understanding.

At the center of his method is what he calls “visual sampling”: gathering fragments from different iconographies and reassembling them into new meanings. This approach finds its fullest form in his Clover project, which resonates with Homi Bhabha’s idea of the “third space.” Meaning in Clover is never stable; it changes depending on how one looks, or from where.

But this strategy raises difficult questions. When does hybridity become ornament? When do borrowed symbols lose their resonance? Zorg doesn’t answer—he leaves the questions open, allowing uncertainty itself to become part of the work. Compared to his earlier Migration Plan (2023), which kept a deliberate emotional distance through non-human figures, Clover feels more exposed. It lingers on the uneasy edge between respect and appropriation.

At the heart of Clover is a triptych oil painting shaped like a window, inviting viewers to move around it. The work hovers somewhere between a picture and a structure, as if unsure whether it wants to be looked at or stepped into. Buddhist, Egyptian, and Christian symbols coexist but resist merging. The work insists that concurrence is not harmony—it’s an ongoing negotiation between memory, tension, and depth.

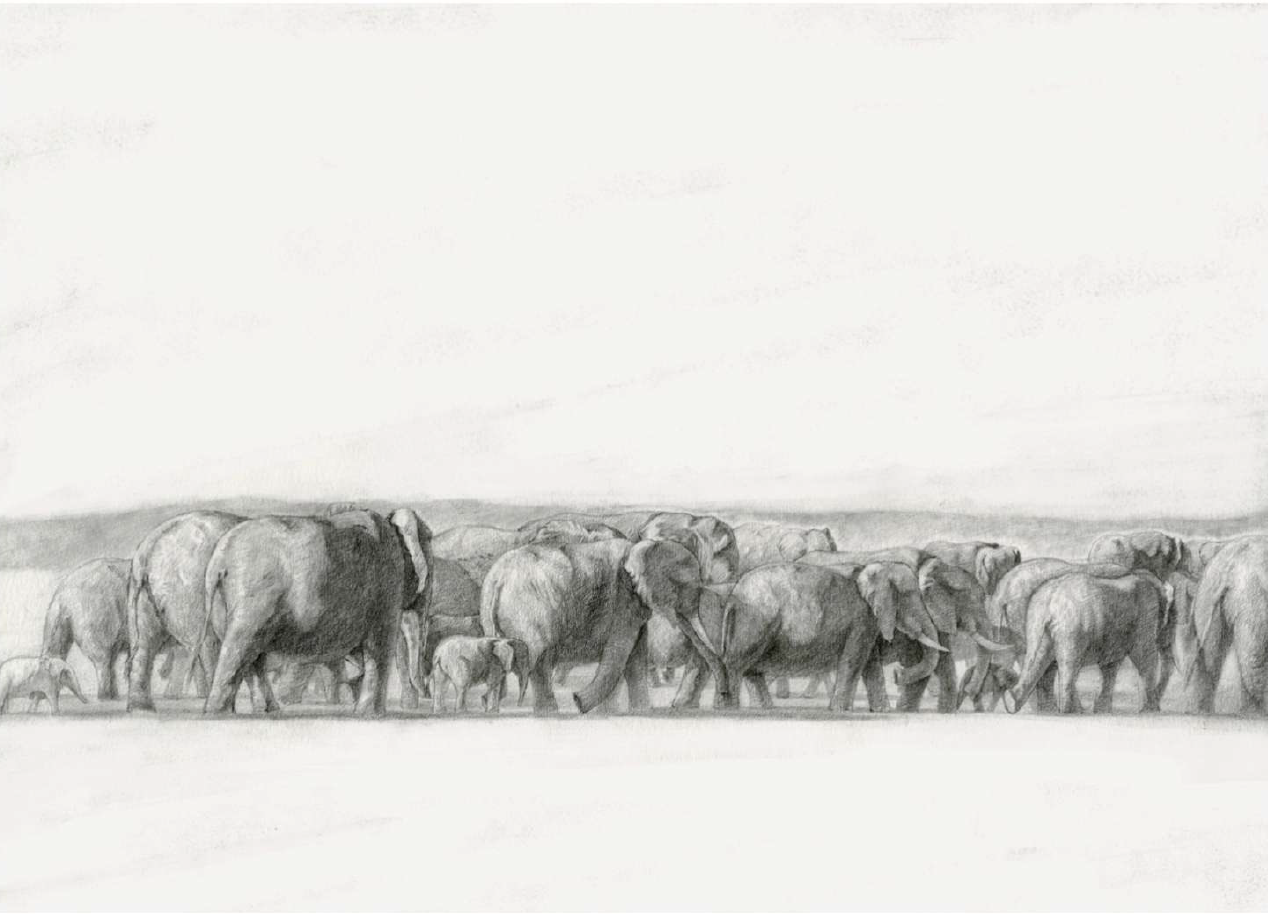

Migration Plan 2023 Drawing

Zorg’s four illustrations—Dianbo, Dongcha, Guankan, and Ganying—draw his ideas into something more intimate and grounded.

In Dianbo, you can feel a quiet pull between surface and depth. The figures have no faces, yet their patterned garments are alive with memory, as if each thread were holding on to a story. It’s a small, almost private reminder of how easily complexity can be flattened when the world demands simplicity.

Dongcha is more fluid. Fragments of Eastern spirituality drift into traces of Egyptian myth, not fusing but brushing past one another. The result is uncertain, like a conversation that keeps changing direction—a play of belief and memory that never quite settles.

Guankan stages stillness against movement: a reflective figure before a wall of arches, behind which horses charge forward. History, it seems, never stands still—it trembles between order and chaos.

Finally, Ganying abstracts the face itself. Rendered in muted tones and cropped tight, it gestures toward a worry that the idea of “universal identity” might erase the particular, lived stories of diaspora.

Left: Dianbo 2025 Oil Painting; Right: Dongcha 2025 Oil Painting

Left: Ganying 2025 Oil Painting; Right: Guankan 2025 Oil Painting

Across these works, Zorg captures the pulse of multicultural London—its noise, its friction, its fragile beauty. Still, Zorg remains cautious. He wonders whether the enthusiasm for hybridity sometimes turns difference into mere ornament. His way of working—borrowing, mixing, but never smoothing things over—feels like a quiet test of what cultural exchange can mean when done with both curiosity and doubt.

The window keeps reappearing in his work as more than just a visual motif. It asks us to think about how we look—and how we allow ourselves to be looked at. In an age obsessed with clarity and definition, Zorg’s work reminds us that coexistence means living with complexity, not resolving it. It asks us, quietly but firmly, to stay with the beauty of difference.

Published March 15, 2025. Edited by Alicia Puig.